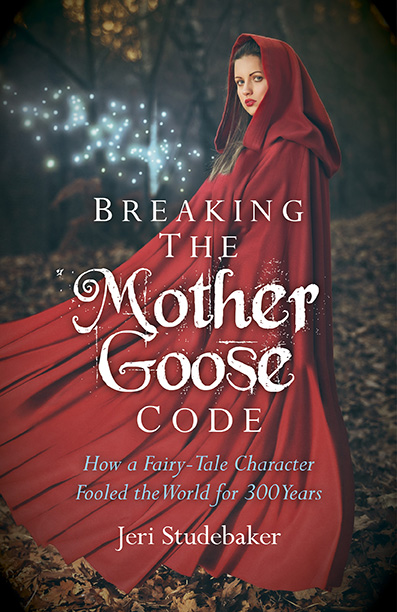

Breaking the Mother Goose Code

For centuries the real Mother Goose has been shrouded in mystery; now, finally, her secret identity is revealed.

For centuries the real Mother Goose has been shrouded in mystery; now, finally, her secret identity is revealed.

For centuries the real Mother Goose has been shrouded in mystery; now, finally, her secret identity is revealed.

Fairy tales, folk tales, legends & mythology, Goddess worship, Witchcraft

Who was Mother Goose? Where did she come from, and when? Although she’s one of the most beloved characters in Western literature, Mother Goose’s origins have seemed lost in the mists of time. Several have tried to pin her down, claiming she was the mother of Charlemagne, the wife of Clovis (King of the Franks), the Queen of Sheba, or even Elizabeth Goose of Boston, Massachusetts. Others think she’s related to mysterious goose-footed statues in old French churches called “Queen Pedauque.” This book delves deeply into the surviving evidence for Mother Goose’s origins – from her nursery rhymes and fairy tales as well as from relevant historical, mythological, and anthropological data. Until now, no one has ever confidently identified this intriguing yet elusive literary figure. So who was the real Mother Goose? The answer might surprise you.

Click on the circles below to see more reviews

I was very curious about this book and decided to give it a try mostly because it is about fairy tales, but I need to clarify I wasn't familiar with Mother Goose before reading it, so my experience may not be the same as that of someone who grew up with her. However, it was fascinating, entertaining, and thought-provoking. Jeri Studebaker explained in great detail her thought process, her analysis, and research as she tried to discover who Mother Goose was/is, the history behind this figure, her influence, historical background, and the messages that could be hidden in her rhymes. I would say my favorite part of Breaking the Mother Goose Code was the rituals, spells and incantations based on the tales, although those are inspired in the Grimm fairy tales......... In short, I loved how descriptive and detailed Breaking the Mother Goose Code is, the theories and ideas it shares, and those chapters on spells and rituals, let me repeat, are pure gold. Although heavy at times, it will be a great reading for lovers of more academic readers. Fascinating from beginning to end! ~ Kyler B. Warhol

“Breaking the Mother Goose Code: How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years”, by Jeri Studebaker Reviewed by Geraldine Charles It is a long time since I enjoyed a book packed full of ideas, research and analysis quite so much, and a great deal of that pleasure has to be down to Jeri’s writing style, which is engaging, witty and never dry or boring. I was sorry to get to the end of the book, having enjoyed even the appendices, and was thrilled to have the bibliography as a brilliant resource. No doubt I will start again at the beginning, this time with Google open by my side as one thing I did regret was a lack of illustrations in such a very visual book. It occurs to me that maybe Mother Goose is not quite so well-known in Britain as in North America: perhaps the name is used more there for what we Brits simply call fairy tales and nursery rhymes? I don’t necessarily agree with every bit of interpretation and Jeri herself is careful to point out when she is speculating. However, much of this type of work and research has to begin from a place of intuition and speculation, the personal remains political as far as Goddess research is concerned. Exploring these liminal places needs careful research, speculation — and intuition; the archetypes may be available to us all but they’re not always so easy to access and have been culturally interpreted and obscured to greater or lesser extents. The idea of coded messages hidden within fairy tales bothers me a little, but the messages are clearly there—maybe not put there in full consciousness but there nevertheless. As a child, I inhabited a world where myth, folklore and goddess archetypes were jumbled together, and on reaching the age at which children are supposed to put such things aside, to join the “real” world of work and study, I managed to sneak an edition of Grimms’ Fairy Tales intended for adults past a drowsy librarian. Reading this left me with an indelible knowing—that there’s an alternative version of reality, a land that would never be accepted in any academic setting, but one we all know; a place of different truths, where the maps are not set but variable and no matter how much people who want “power over”, hierarchy and to keep women in their supposed place try to censor and sanitise, the beloved fairy tales remain as signposts and clues to a different reality. But somehow I forgot that other world for years, and thought of fairy tales mostly in feminist terms, noting, for example, that princesses often stay put in the family castle while princes wander about in search of a bride – evidence that sovereignty, the land, was passed down through the female line and not the male. Ideas which are still valid, but only part of the truth— that much goddess knowledge and wisdom could be passed down through fairy tales and rhymes ostensibly intended for young children, but which speak to us all. Thank you, Jeri, for reminding me of these alternate worlds! Overall? I’m excited and inspired. Whatever the “truth” of the stories, of hidden codes and meanings, the book is a fantastic framework for future research and thought and I know I will refer to it many times. “Breaking the Mother Goose Code” is published by Moon Books and available from Amazon. Geraldine Charles is the founder and editor of Goddess Pages. She is also a Priestess of the Goddess, a founder member of the Glastonbury Goddess Temple and a former Glastonbury Goddess Conference ceremonialist. ~ Geraldine Charles (Goddess Pages), http://www.goddess-pages.co.uk/breaking-the-mother-goose-code-how-a-fairy-tale-character-fooled-the-world-for-300-years-by-jeri-studebaker/

Title: Breaking the Mother Goose Code: How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years Publisher: Moon Books Author: Jeri Studebaker Pages: 319 pp Price: $26.95 (paperback) / $8.49 (ebook) This book reveals Mother Goose as a disguised Mother Goddess figure. Fairy tales, folk tales, and nursery rhymes transmit pagan and heathen information in hidden form, often through symbolism. I recommend this book for both scholarly and general readers. The introduction tells how author Jeri Studebaker wrote the book, and goes into her personal experiences, some of which are in the category of personal gnosis. The author began with the image of Mother Goose in folk art, including many images of her dressed as a witch with a black cone hat and broom. The tale of the puzzle box with the image of Mother Goose riding through the sky in a wagon is delightful. The author connects Mother Goose with goose-footed goddess figures, such as Queen Perauque, and tells us that one of the origin stories of Mother Goose is that she was Goosefooted Bertha, the mother of Charlemagne. Later, Studebaker discovered that Jacob Grimm said Bertha is a name derived from the goddess Perchte, a regional variation of the goddess Holda, who is often seen in Heathenry as an aspect of Frigga. The book started to lose me by equating Holda with Hela, Cinder-Ella, and Harlequin purely on the similarity of the sound of their names. I was prepared to be disappointed, especially when the author referred to the heathen and pagan societies of pre-Christian times as “pre-patriarchal,” which flicked my fluff-o-meter, but once past the introduction and into the main body of the book, the author makes her case for each of her contentions with plenty of backup from primary and secondary sources. The book examines the one traditional poem that has Mother Goose in it, which contains symbolism such as a golden egg. The author relates the bird and egg symbol to the story in Egyptian mythology of the bird goddess producing the sun egg. The book goes on to examine fairy tales collected under the Mother Goose title, beginning with the earliest such collection, by Perrault. Perrault’s book collects several fairy tales with Fairy Godmother figures who rescue and mentor the main characters. Studebaker proposes the Fairy Godmother is a disguised Mother Goddess. Studebaker relates Mother Goose to both Germanic and Greco-Roman goddesses, and contends that the Mother Goose figure grew out of a union of such goddesses during the time of the fall of the Roman Empire. The Germanic goddesses include Bertha / Perchte / Holda, goddess of spinning and motherhood, and Hel or Hela, the Germanic / Norse goddess of death. The Greco-Roman goddess is Aphrodite / Venus, who was depicted in art riding a goose like Mother Goose does in art and in her one poem. In relating Harlequin to Hellequin and thus back in time to Hel, the author equates Hel with Holda. She contends that since the female Hellequin turned into the male Harlequin, Mother Goose’s son Jack must be androgynous like Aphrodite’s son Eros. In explaining that the goddess Hel has the same name as her realm Hel, the author makes the common mistake of identifying Valhalla as a “better place” than Hel, but that is tangential to her point, and does not detract from her overall thesis. Going forwards in time again, Studebaker traces the development of the Harlequin character. The Mother Goose and Harlequin play by Dibdin fleshed out the disjointed narrative of the one Mother Goose poem, shedding light on the character’s motivations and other questions raised by the poem. Connecting witchy Mother Goose art, particularly of the 1800s, to the Bird Goddess, Studebaker suggests the American Halloween witch’s large, pointed nose may be a remnant of a depiction of a bird’s beak, such as the mask of the Schnabelpercht, a bird goddess figure in midwinter celebrations in Austria. In continental Germanic culture, both the goddess Holda and Mother Goose are called Frau Gode, which means Mrs. God. The Neolithic bird goddess had the body of a woman and the head of a bird, with a beak and wings. Marija Gimbutas related the bird-like characteristics of the wings of Freya, the Valkyries, and Holda to the Old European bird goddess who both gives and takes life. As the Valkyrie is a psychopomp, and Freya as head of the Valkyries and an owner of the land where half the battle slain go is in some ways a death goddess or crone-witch death figure, whereas Holda and Mother Goose seem more oriented to child end of the lifecycle, it appears the function of the bird goddess as giver and taker of life was slightly split in post-Stone Age times. Gimbutas believed that Holda and Brigid are survivals of pre-patriarchal, Neolithic goddesses. In the next section of her book, Studebaker goes into the competing values of Stone Age society, which she terms pre-patriarchal, nonviolent, and abundance-oriented, the values of Old Europeans (what heathens like me would call Vanic values), and iron age civilization, the patriarchal, warlike, and scarcity-oriented culture that arrived with the migration of the Indo-Europeans (what heathens would call Aesiric values.) She traces these values through history and through folk culture. Studebaker examines various nursery rhymes and the lessons they teach, which were at odds with the official values of the 16th through 19th centuries. She then gives fairy tales the same examination under her lens of seeing nonviolence and joy as female, goddess-oriented values, and violence and duty as male, by this time Christian-overlayed, values. Studebaker outlines theories about fairy tales. She relates various fairy tale characteristics to a pre-patriarchal, goddess-centered religion, for example, by totaling the number of appearances of specific animal motifs in fairy tales. Fairy tales are examined as mythology, as shamanic spirit journey, and as magic spell. The animal helpers in fairy tales are spirit guides. Telling the tale is casting a spell; spell once meant story. The book contains several examples of fairy tales as spells for specific purposes. For each story, the author suggests ritual tools based on objects in the story. For example, the story of Hansel and Gretel has white stones in it as trail markers, and Studebaker suggests using a white stone in a spell to find a lost child. Studebaker suggests incantations based on the rhymes in each story, ritual sequences based on the plot, and so forth, making each fairy tale a complete spell. These are spells that one could actually perform. This part of the book will be of great interest to witches seeking to use fairy tale magic. There are spells for healing, protection, and so forth. Once one reads through the examples and gets the hang of it, one could apply this method to other fairy tales to yield rituals of various kinds. The book then goes into a shocking conspiracy theory involving foundling homes and the Inquisition. Veering back to the subject of coded messages in fairy tales, the book tells how contemporaries of Perrault retold fairy tales as commentaries on then-current politics as a means of getting past censorship. Perrault would have been familiar with these coded, modernized versions of fairy stories when he set out to write the first Mother Goose book. He may have been aware of pagan content in the fairy tales he recorded. Studebaker contends that Perrault may even have been a secret revolutionary. Perrault did not put his name on his Mother Goose book and disguised his association with it. This is usually explained as embarrassment about being associated with children’s stories, as Perrault was already known as a serious writer for adults. Studebaker raises the question: was Perrault not embarrassed, but afraid? He was writing in a time period when they were still burning witches. As he lived in a time and place where it was legally chancy to be a Protestant, let alone a goddess worshipper, fear of witch persecution would have been perfectly reasonable. Was Charles Perrault a witch? The book has a number of appendices, including a handy list of fairy tale symbols and their meanings. There is a long bibliography, index, and so forth, as one would expect in a serious academic work. This book is academic in style everywhere but the introduction; however, the concepts are presented clearly and any terms that a reader without a background in feminist studies and literary theory may not be familiar with are explained thoroughly. This may be a challenging read for a reader used to reading at the level of American Family Newspaper style, but I think a general reader can follow it, especially as the subject of fairy tales will be familiar to those interested in the topic. Anyone interested in fairy tales, folklore, and folk magic should read this book. Breaking the Mother Goose Code is a revelation for anyone interested in finding more information about the European goddesses than has survived in the official lore written down by and for men. I highly recommend this book for both academic and general audiences. [Erin Lale is the Acquisitions Editor at Eternal Press and Damnation Books. Her writing and publishing career began in 1985. She has an extensive list of published nonfiction, fiction, poetry, etc. In the print era she was the editor and publisher of Berserkrgangr Magazine and owned The Science Fiction Store, and she publishes the shared world Time Yarns.] ~ Eternal Haunted Summer , http://eternalhauntedsummer.com/issues/autumn-equinox-2015/breaking-the-mother-goose-code/

Is the Mother Goose of fairy tales the Great Goddess in disguise? This very readable book takes the reader on a journey of exploration to find out, and goes into some fascinating byways; for instance why may the statue of a goose-footed woman be found in several old French churches? I did have issues with the theory of a matriarchal golden age before patriarchy arose in all its nastiness and spoiled it all, but that notwithstanding it's a good read if you enjoy looking into folklore... which I do! ~ The Inner Light, Autumn Equinox 2015 ed. Volume 35 No.4

The Magical Mystery By Kate Merrill on September 4, 2015 Format: Paperback As one who reads only fiction, especially mysteries, it is astonishing that Breaking the Mother Goose Code captured my imagination and imprisoned it throughout the adventure. A mystery in its own right, the book explores the origins of the Mother Goose character, her nursery rhymes and fairy tales, and finally exposes the grand bird as an amalgam of Aphrodite, Holda, Frigga, Mari, and the Celtic Goddess, Brigit. Through her exhaustive, yet spellbinding research, Studebaker puts her impressive anthropology and archaeology credentials to work, along with her Goddess expertise, to prove that Mother Goose was a code used by pre-Christian, pre-patriarchal cultures to keep their magical, peace-loving, female-centric religions alive through the Inquisition and witch burnings. For me, Studebaker’s research itself was the hook, the thrill. Her Sherlock Holmes-like sleuthing sorts and displays the evidence to reach a convincing conclusion. As the author dances through the enchantment of the fairy tale verses, explores Mother Gooses’ evolution through art and theater---all presented with Studebaker’s wry sense of humor and gentle bias to a feminist point of view---I was awed by her dedication and absolute determination to arrive at a balanced, scientific thesis. All this, yet the story remained a fast-paced page-turner. Not only did it transport me back to my childhood by reminding me of the almost-forgotten wonder of the Mother Goose stories, but as an adult, it enriched these tales with a deep new understanding of the underlying meaning of Mother--- mighty Goddess in disguise, ancient symbol for religions and gentler cultures which might have been lost to modern man---if not for Mother, and this book. ~ Amazon.com, http://www.amazon.com/Breaking-Mother-Goose-Code-Fairy-Tale-ebook/product-reviews/B00SI6J74I/ref=cm_cr_dp_synop?ie=UTF8&showViewpoints=0&sortBy=bySubmissionDateDescending#R1O53N7M3F9U3X

Book Reviews Breaking the Mother Goose Code: How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years Written by Elizabeth Hazel Published: 23 August 2015 This is a first-person account of the process of researching the mystery of Mother Goose. Studebaker shares the clues along the path to discovering the true identity of Mother Goose. This, in turn, reveals the covert purpose of fairy-tales and nursery rhymes. The earliest appearance of Mother Goose in published books of fairy tales is examined in detail, as are numerous historic book-cover depictions of Mother Goose. The transformation of Mother Goose into a hag-like witch is a fascinating bit of commercial illustration history. Part I outlines the history of Mother Goose's appearance in literature and the stories associated with her. Part II presents an in-depth examination of the hidden goddess and magical lore encoded into fairy tales. There are numerous appendices that include synopses of Perrault's fairy tales, a glossary of fairy tale code words, discussion questions. There is a juicy bibliography and an index. Chapter 13 describes the magical spells and incantations contained in fairy tales. The author gives suggestions for how these might be performed. The extensive bibliography substantiates an impressive labor of research by the author over several years. The book's thesis is complex because the clues are widely dispersed, making it difficult to navigate through the topic in an ordery manner. The persistence of the old religion and magic in Europe has only recently been verified, primarily in university research papers, journals, and scholarly treatises by writers like Pennick and Lecouteux. This book is a great introduction to Crafters who seek more information about the legacy of the Goddess in legend and magic that’s encoded in fairy-tales. For individuals taking their first steps into the transmission of ancient Goddess lore, Studebaker provides a finely-written and accessible account that demonstrates how researchers gather tiny pieces to assemble a picture of historical events and move forward into the deductive process. For readers who are familiar with the transmission of pre-Christian European Goddess spirituality and magical traditions, this book may repeat some material that has already been covered in other books. Advanced students of myths and fairy tales will find the specific details of Mother Goose's artistic and literary transformation quite valuable. This book is recommended to readers who are curious about the ubiquitous figure of Mother Goose as her literary and artistic progress from the late Middle Ages through contemporary times. It is thoroughly traced and presented in an entertaining manner. ~review by Elizabeth Hazel ~ Facing North, http://facingnorth.net/Witchcraft/breaking-mother-goose-code.html

Intriguing Scholarship – or the Mother Goose you never knew! July 3, 2015 · landisvance A Review Breaking the Mother Goose Code:How a Fairy-Tale character Fooled the World for 300 Years Studebaker, J. (20015). Washington:Moon Books As I began to read Jeri Studebaker’s thoughtful exploration of the creation, development, and use of fairy-tales I had the fleeting thought: ‘why didn’t I know this before?’. Her thesis that fairy stories are coded works that safeguard the holy mysteries of early goddess-based religions in the face of oppression and suppression felt so right to me that it was an experience of knowing what I didn’t know I knew. I have been on a personal quest to re-discover the Goddess for some time now and this addition to my library has given me a touch-point – the Goddess never really went away, she just went into hiding, and now in our post-modern society it is safe for her to return to view. Studebaker has engaged in a work of scholarship and with the wealth of information she has assembled has organized her book into two sections. The first section explores her thesis that Mother Goose is a representation of the Goddess drawn from a time before the introduction of patriarchy into society and its banishment of the thoughts and values that preceded it. The only nursery rhyme that we have about Mother Goose is found in a book by a Frenchman, Charles Perrault, Tales and Stories from Times Past, or Tales of Mother Goose published in 1697. Studebaker uses this tale as the foundation for her research, taking her cues on what to look for and where to look. Were there goddesses associated with geese and, if so, who were they? Studebaker attempts to uncover the meanings behind the imagery of this tale: goose, owl, dove, moon, gold, goose eggs, sea, and forest. She also looks at the dynamic of parent/child interactions and the character of the Harlequin. She then builds an argument that indicates the probability of Mother Goose as representing the goddess Holda/Perchta or Aphrodite/Venus. In addition to parsing the meaning of the Mother Goose story, Studebaker looks at the metamorphosis of the graphic image of Mother Goose across time. While the graphic image within the original 1697 work depicts Mother as a comely young woman, by 1764 she was shown to be an old, crippled, sharp-faced crone. Such a change cannot be overlooked and expresses the changes within society that is seeking to turn this tale into a warning. Her exploration of this leads her to the discovery of the missing link of these two extremes, a play dating from 1806 titled Harlequin and Mother Goose; or, the Golden Egg! A Comic Pantomime, by Thomas Dibdin. that portrays Mother as a supernatural being with great powers. It is also the first time, in print, that Mother flies on the back of a goose. It is thought that the play draws on older sources and traditions that are no longer available to us, and it certainly fleshes out the original story. The last piece of this analysis focuses on the movement within society, following the Christian conquest of Rome, toward a patriarchal and hierarchical orientation. Studebaker offers interesting correlations between major religio-political events, such as the Inquisition, and the morphology of the fairy-tale. Studebaker builds, brick by brick or fact by fact, a strong foundation to support her thesis and, having done so, then proceeds to analyse each of the Mother Goose tales accordingly. The Tales are then grouped according to the hidden meanings she uncovers: History and Future of Europe’s Old Religions Creation, Cosmology, and Theology Spells and Incantations Rights and Wrongs All of this is supplemented by a number of appendices, footnotes, and bibliography that offer the reader further resources should she/he wish to delve further. I enjoyed this book and found it to be a good addition to my library. While there were a few points with which I disagreed or a few arguments that I felt should have been taken further, the scholarship is excellent and the topic intriguing. I recommend this to both seekers on the journey and budding scholars interested in a starting point. The book encourages critical thinking in a new way, and I have found that my awareness of the shaping by a dominant culture of what topics are discussed and the shape those discussions are allowed to take has been broadened significantly as a result. ~ Spirit Mountain Wilds, http://spiritmountainwilds.com/2015/07/03/intriguing-scholarship-or-the-mother-goose-you-never-knew/

THIS IS A VIDEO REVIEW * * * * * ~ Danni Niles, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ii1I6qgf0hw

Danni Jeri Studebaker's Breaking the Mother Goose Code: How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years* goes into great detail about the possible origins and uses of the epic character of Mother Goose. She traces the history of folklore, goddess worship, and politics in regards to the development of Mother Goose. All of this history is well cited, and readers can easily find the cited sources for themselves. I appreciated the emphasis on clear research. Even with this focus on the academics of the question, the author's own curiosity and process comes through in a lively and engaging voice. The first part of the book focuses on the character of Mother Goose. Mother Goose doesn't appear in every nursery rhyme or every culture in the same way. The author does a splendid job of tracing the different aspects of Mother Goose (age, flying on a goose, etc.) back to their original inspiration. The author also makes a strong case for how and why this character could be a Goddess figure. The second part of the book focuses on the social and political forces surrounding the creation and distribution of Mother Goose. The theory is that Mother Goose, a representation of the Goddess, was hidden in nursery rhymes to help preserve a Goddess culture. I found the chapter on how specific stories could have been instructions for shamanic magic for healing, love, protecting children and finding stolen objects to be of particular interest. There does seem to be some value to an interpretation like that. This is a sparse simplification of a great many pages of specific details and intriguing research into the use of Mother Goose over centuries. At the end of the read, which was enjoyable from page one, I'm not sure I found myself wholly convinced. There were parts that sounded so perfectly logical and others that seemed more far-fetched. I was convinced that Mother Goose is a Goddess figure. I was also convinced that some of the stories and nursery rhymes could contain hidden messages. I'm not sure I'm convinced that Mother Goose was a deliberate tool used to hide away Goddess worshiping cultures. For me to believe this theory would have to do further outside research. If you enjoy folklore, Goddesses, or history, this is a must read. It's wonderful to get a book that is more "Pagan" without being about the same five topics, told in the same way that most Pagan books are. I think most people will enjoy it. Even if you disagree with the author it will give you a great deal to think and chat about. *I received a .pdf copy of this book for free in order to give a review. All opinions and thoughts are my own. (less) ~ Goodreads, https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/23590847-breaking-the-mother-goose-code#other_reviews

Book Review: Breaking the Mother Goose Code I have been a fan of fairy tales since I was little. I'm not a huge collector, but I do have a small collection of tales, and I always thought it was both fascinating and strange how violent some were in different versions (and how tame the modern mainstream versions are). I was very excited to start reading Breaking the Mother Goose Code, as I have always thought of fairy tales as teaching stories, and learning more about what they taught, especially in a Pagan light, called to me. I found a lot of new ideas in this book. I thought it was really interesting how Jeri starts by examining the image of Mother Goose herself. She details her journey of looking for and comparing different pictures of Mother Goose and how the depictions changed over the years. I had never really thought about the figure of Mother Goose much, and was fascinated to read about the many faces she wore. Jeri then goes on to try to uncover which Goddesses might be hidden behind the name Mother Goose. It was a very interesting read to follow these breadcrumb trails and to see the ways that different deities in different areas of the world might have been linked to fairy tales. Being that her name is Mother Goose, Jeri also looks at the folklore and magic surrounding geese, ducks and swans (as they are often used interchangeably). Not only did I learn a lot about different deities with goose legs (which I hadn't been aware of!), but also the really interesting swan pits, and theories about what they might have been for. The image pained in my head, of women building and caring for these pits, while trying to bring new life into the world, is a beautiful and hauntingly sad one. Where I really got drawn in was in her analysis of the tales themselves. Jeri looks at the structure of the tales, how most of them seem to follow a archetypal framework. I thought the connection to shamanic trance journeying was an interesting way to look at it. I also really enjoyed her connection between the progression of the main character of the story and the learning process that a magical practitioner might go through. Another really interesting perspective detailed in this book is that fairy tales might be used as actual spells. By taking key passages, especially if they rhyme, as well as items that featured in the tale, one might use the story as the framework from which to enact a spell aligned with the focus of the story. I can definitely see how fairy tales could inspire this type of reconstructed working. A lot of information was presented in this book. It is obvious that Jeri did an enormous amount of research, and she shared many of the things she found with her readers. She asks a lot of questions, and encourages the reader to continue asking questions. I am definitely going to be thinking about fairy tales in a different way after reading this book, and I look forward to revisiting some of my favorite tales through this new perspective. ~ Kylara's Musings, http://kylarathought.blogspot.com/2015/03/book-review-breaking-mother-goose-code.html

This book gives a fresh and fascinating angle on examining ... By Amazon Customer on March 17, 2015 Format: Kindle Edition This book gives a fresh and fascinating angle on examining fairy tales. The author takes the idea that Fairy tales contain hidden teaching stories about Goddess worship and runs with it. Jeri examines not only the tales themselves, but the ways in which they have changed over the years, and the historical events that occurred at the times these changes happened. She looks at not just the words of the tales, but the way in which they were shared or published and the images that were used on the cover. She shares her research about the different Goddesses that are linked to Mother Goose herself. Themes withing the tales were explored as well as who the characters might be representing. The book delves into the lessons that the tales teach us, and how they reflect on the mindset of the people telling them. Jeri shows ways that the tales can be used not only as teaching stories, but as a framework for magic itself. By the end of the book, I found myself thinking about fairy tales in a whole new light, and excited to re-read my favorites (and discover new ones) with fresh eyes. ~ Amazon.com, http://www.amazon.com/Breaking-Mother-Goose-Code-Fairy-Tale/dp/1782790225/ref=sr_1_2?ie=UTF8&qid=1416502479&sr=8-2&keywords=Jeri+Studebaker

I did not really expect to be convinced by Jerri Studebaker’s book about finding signs of ancient Goddess worship in fairy tales. I’m just not the sort of person who is easily persuaded by much, and the sleight of hand history of Dr Anne Ross, and the chicanery of Robert Graves have left me resistant, to say the least. I’m very wary of circular logic, too. Go out looking for evidence of sacrifice and you’ll see it any time there’s a dead person. Go out looking for Goddess survivals and you can all too easily infer them into anything with breasts. I ended up persuaded to a degree that surprised me. What makes this book such an interesting and provocative read isn’t, I thought, the main thrust at all. It’s the details. The histories of where nursery stories have come from and how they’ve changed over time. The correlations between fairy stories and other major cultural shifts. I’d not thought before about the way in which many fairy stories are really at odds with Christian stories. I was, I confess, too busy being cross about the princesses. But now I have reasons to rethink those, as well. The historical correlations Jeri Studebaker brings together in her book are intriguing. There are many unanswered mysteries here, that will leave you wondering. She has evidence for the political use of the fairy story as a way of making commentary, and the literary place for the fairy tale in Europe as well. That’s without getting into the issues of goose footed women, egg laying, and shamanism. Oh, and magic spells. And how we might envisage a non-patriarchal world. I love this book because the author is cautious about her claims, and keen to remind us when she is speculating and the limits of what the evidence can support. Speculation is so much more enjoyable when we hold our uncertainties with such honour, I think. At this point, whether or not Mother Goose is really, historically and provably a goddess survival seems a lot less important than what we try to do with her stories, and other such stories, moving forward. It is in the nature of stories to change and evolve over time, being re-imagined to fit the new context. Stories that survive are often stories that can be adapted, or that give us powerful archetypes to work with. So the question to ask may really be, how do we want to work with those archetypes in the first place? What stories do we want to tell, and why? Do we understand the implications of the stories we are sharing? For me, the book raised another question as well. (Bear in mind here that I am a maybeist, not a theist nor an atheist.) If religion is imagined into existence by people, as well it might be, then to connect with the religions of our ancestors we need their stories, or whatever fragments survive. Take away its stories and Christianity ceases to exist. If religion is based on the experience of living, then through shared experiences, we can come to similar conclusions as our ancestors did. If we reverence the things life depends on, then we can find our way to the importance of the mother, the goose, the eggs and all the other ideas about life fairy tales can carry. If the deities are independently real and active, then of course things that look like them will keep turning up in people’s stories and ideas, for all the same reasons that they turned up in the first place – because they are offered to us by the divine as inspiration. I don’t know. I still don’t know. I’m fine with this, and I enjoy books like this one that are able to challenge my carefully chosen uncertainty. ~ Nimue Brown, https://druidlife.wordpress.com/2015/03/14/breaking-the-mother-goose-code/

14.3.15 SAUCE FOR THE GOOSE Jeri Studebaker: Breaking the Mother Goose Code: How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years. Moon Books, 2015. All of us are familiar with fairy tales, usually associated with a warm glow of childhood memories when we first heard them, and then heard them again and again. They are somehow imbued in our consciousness as enduring archetypes and metaphors for the underlying principles of life itself, such as the struggle between the forces of Good and Evil, and the quest for true Love. In this easily readable and friendly record of her extensive research, American author Judi Studebaker takes us with her on her personal odyssey to discover who or what was ultimately behind the emergence of Fairy Tales in general, and Mother Goose in particular. What if Mother Goose was actually the ancient European, Egyptian, or even Universal Mother Goddess in disguise? The author eventually reaches just this conclusion which she intuited at the start of her interest in Mother Goose, but to her credit does it by following the admirable path of thorough research, historical verification, and the scientific method of testing her theory. It has to be said that Mother Goose appears to resonate more with Americans than those of us raised in Britain. What we call "Nursery Rhymes" here are often referred to as "Mother Goose Rhymes" over there. However, we are here dealing with matters far more serious than mere children's rhymes and stories, for there was a time in European history when holding ancient pre-Christian beliefs and practices, or even being suspected of them, could result in torture and death. To quote directly from the book: "...it became unsafe even to talk privately about pre-Christian religion - especially after the witch persecutions began. In fact, it got so bad that eventually a kind of mania settled over many parts of Europe. It seemed everyone suspected everyone else of being a witch." The author goes on to explain, with several references to other researchers, that there were well-founded fears of those who might use black magic to harm others, but that "Europeans also believed in what are variously called white witches, cunning folk, healers, shamans, and several other terms designating people considered able to use magic in a positive way to satisfy a multitude of human needs." In short, the fundamental message of this book is that Fairy Tales appeared in Europe at just the same time that Christianity was reaching its most aggressively Patriarchal guise. They were timeless allegories of of a long-lost civilisation that was Matriarchal in character, so they celebrate the female in her three main stages of Princess (virgin girl), Mother (adult woman) and Crone (woman having attained wisdom, knowledge and power, represented as a witch). In Fairy Tales, frogs may be princes in disguise and crones are princesses in disguise, teaching us not to judge by appearances and to have compassion for all our fellow beings, as far as circumstances allow. They are timeless repositories of wisdom, reminding us that beyond the mundane world there is a realm of magic and all possibility. Ultimately, the Goose represents the Goddess, the mystical divine feminine entity that laid the Cosmic Egg, all of Creation. -- Kevin Murphy ~ Magnolia Review of Books, http://pelicanist.blogspot.com/2015/03/sauce-for-goose.html

A couple of weeks ago Nimue Brown asked who among her readers would interested to review books on their blog. Although I’m by no means a blogger with a large audience, I am a voracious reader. So I applied and to my surprise, I was kindly added to the list. Last week I received my first book to review: Breaking the Mother Goose code by Jeri Studebaker. I find that when I make whimsical but heartfelt decisions quite like this one, the universe surprises me by what it throws my way. I have been working, reading and thinking about subjects related to the matters that are discussed in this book, the true origins and meanings of European myths. Breaking the Mother Goose code could not have come at a better time. The book proposes the possibility that Mother Goose is a literary figure that was invented to hide the European Mother Goddess. She emerged in books and print at a time when every last remnant of a non-Christian culture was persecuted and almost completely eradicated. The author also asserts the idea that these fairy tales and nursery rhymes hide a treasure: a memory of a wholly different, pre-patriarchal society. The author’s style of writing is very accessible. She has read and researched widely but the book pleasantly lacks a scholarly tone. I thoroughly enjoyed reading this book and was often amazed by the connections and conclusions the author draws. Some of the conclusions that are drawn, however, seem to belong to the realm of speculation. The author is upfront about this. Fairy tales are by their very nature an elusive beast, because they hail from an oral tradition. It is hard, if not impossible, to know their pedigree. However, in many parts of Europe, the influx of Indo-European people, allegedly bringing and spreading their patriarchal culture along with their languages, pre-dates these fairy tales by thousands of years. That is why I find it problematic to regard certain fairy tales as relics from pre-patriarchal times. The strict division between patriarchy and egalitarian societies is by no means an undisputed fact. The same goes for the assertion that the fairy tales are visions of shamanic experience or transcribed spells. I find these ideas very interesting, but they can not be proven. They scream for even wider exploration though! The author does build up a strong case for the fact that these fairy tales were deliberately hidden by Charles Perrault, the literary father of Mother Goose. The one thing that did bother me was the lack of illustrations. Such a book most certainly deserves to be illustrated luxuriously, especially because there are many references in the text to depictions of goddesses and the literary character Mother Goose. Apart from that, anyone interested in fairy tales, pan-European cultural motives and Goddess religion will love this book. ~ Linda Boeckhout in book review, https://theflailingdutchwoman.wordpress.com/2015/03/07/breaking-the-mother-goose-code-a-book-review/

When asked to review this book I jumped at the chance. Having read Jeri Studebaker’s Switching to Goddess, I had a feeling I would love this book on the myth of Mother Goose. I was not disappointed. Half way through Chapter One I promptly ordered myself a copy of this gem of a book. I devoured this fascinating read in a matter of days and am thrilled to have this in my esoteric library. Breaking The Mother Goose Code is the Da Vinci Code of nursery rhymes and fairy-tales. Jeri Studebaker takes us on an adventures ride in search of what she believes to be the true meaning and origin of Mother Goose. With her wealth of knowledge Jeri draws the reader into the fairy-tale realm of nursery rhymes, digging deep into the history and mystery of Goddess worship concealed deep within the character of Mother Goose. Jeri Studebaker traces the identity of Mother Goose through the ancient history of the Mother Goddess, connecting such goddesses as Holda and Aphrodite to this captivating character. By linking the goose and other sacred animals featured in nursery rhymes with goddesses of the world she uncovers the mystery of Mother Goose. Jeri shows us that the visage of Mother Goose changes throughout time. She is shown as a kindly mother figure and as a typical old hag. By deciphering the codes hidden within such tales as Cinderella, or the Little Glass Slipper, The Sleeping Beauty in the Wood, Little Red Riding Hood, and Blue Beard, Jeri Studebaker discovers what might be the true identity of the characters, showing that the heroines of these tales can be seen as code for Mother Goddess. She covers many goddesses, some of which I would never have thought of connecting to Mother Goose, showing how the image of the Mother Goddess and Mother Goose changes with the times we live in. There are some intriguing chapters in Breaking The Mother Goose Code, all of which add to the adventure of the search for the esoteric meaning of fairy tales and nursery rhymes. Part One goes into great detail of the origins of the Mother Goose figure while Part Two digs deeper into the mystery of the tales. Chapter 13 (one of my favorites) uncovers the magic and charm that can be found in these fascinating tales. I give Breaking The Mother Goose Code two thumbs up. Jeri Studebaker has done a wonderful job of opening my mind to the hidden gifts veiled within fairy tales. The amount of research she put into this treasure of a book is astounding. I find myself searching more for the hidden symbology and imagery while reading the old myths and tales of the Mother Goddess. I’ll be turning to this book often for my own research on the magic and charm that can be found in some of my favorite tales of fairy. - See more at: http://paganpages.org/content/2015/03/book-review-breaking-the-mother-goose-code-by-jeri-studebaker/#sthash.7LWbGWe6.NwouhMMr.dpuf ~ Author Vivienne Moss, http://paganpages.org/content/2015/03/book-review-breaking-the-mother-goose-code-by-jeri-studebaker/

Studebaker's Breaking the Mother Goose Code was another great read, advancing on the basis of impressive research the thesis that the Mother Goose fairy tale was originally designed to communicate Pagan beliefs about the Great Mother Goddess at a time when it was not safe to publicly do so. Although she may not agree with all of the following details, her work has led me to think that some Pagans of the late Middle Ages were aware that a Great Mother Goddess was behind a number of different goddess-figures, and they cleverly combined these goddess-figures into the Mother Goose character in order to protect her identity. Mother Goddess must have soothed Pagans with memories of a better time, before the Indo-European patriarchal societies hurled us off the cliff into intolerance and greed. Indeed, the playful, adventurous and familial Mother Goose rhymes lure us all to a lifestyle that's long been forgotten. This is a case that I'd like to sink my Bayesian teeth into, and calculate the probability of her thesis given the facts she brings to light. I may share my results here, but I couldn't usefully perform the calculation without divulging much of the book's detail--and, thankfully, there is a lot of detail! However, I will say that one of the many virtues of Studebaker's case is her method of presentation, whereby the facts are compiled until it becomes abundantly clear that they're suspiciously coincidental unless she is correct. Whether other experts on Mother Goose folklore are ultimately persuaded by her argument or not, I feel it's the best explanation available, and thus worthy of our respect and belief. It's some fun and interesting detective work! ~ Steven Dillon, http://paganphilosophy.blogspot.com/2015/02/take-that-reading-list.html

TUESDAY, JULY 07, 2015 REVIEW: Jeri Studebaker's Breaking the Mother Goose Code Breaking the Mother Goose Code: How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years by Jeri Studebaker (Moon Books 2015), trade paperback, 319 pages. Also available as an e-book. Breaking the Mother Goose Code is written with a scholarly approach, yet in a style and language that is easy to understand. The book seemed to me to be, in parts, like a mystery novel as Jeri Studebaker tracks down the connection between goddesses and Mother Goose traditions, tales, and poems and songs, as well as, in the second part of the book, other fairy tales. In the Introduction she poses several questions that people have asked about Mother Goose and then writes, “The answer to all these questions is, we don’t know for certain. Mother Goose is an enigma lost in the mists of time. But she did leave a few telltale clues to her identity. . . .” Studebaker goes on to summarize the best know of these “telltale clues.” Then, in chapter 1, “Beginning My Search for Mother Goose,” she adds to them some of her exciting research whose results surprised even her. The beginning phase of the research climaxed on a day in 2012 on which she was able to bring together information from items she found on eBay with material from her previous readings. This led her to conclude that Mother Goose represented a melding of several different goddesses from different cultures. Yet, she writes, questions remained: “How was the knowledge of the connection lost? Was it simply the result of a loss of interest through time? Was the creation of Mother Goose an intentional plot to disguise and best serve this goddess during a time when it was dangerous – and frequently lethal – even to mention her name? Did Mother Goose fairy tales carry coded messages left for us by our pre-Christian ancestors during a time when non-Christians were routinely rounded up, roped to stakes, and roasted alive? If so, what exactly were our ancestors trying to tell us?. . . If Mother Goose was code, what was the point of dressing her as a witch?” In the next chapters of Part I, she explores a number of these clues including the only nursery rhyme about Mother Goose; goddesses Mother Goose resembles; the connections among Harlequinn, Hellequinn, Helle, and Holda; representation of Mother Goose in art; other evidence that Mother Goose was a goddess; whether Mother Goose was a pre-patriarchal goddess; and secrets hidden in nursery rhymes. Studebaker has a rare gift for turning complex concepts into colloquial and entertaining explanations. She uses this gift sparingly, yet effectively, in this book. For example, in chapter 4 when explaining the relationship between Aphrodite and Mother Goose, she writes: “… some writers think Aphrodite began as a powerful goddess who was gradually besmirched by the Greeks and Romans. … we’ve been told Aphrodite was a somewhat empty-headed physical knockout. Also though, according to the Greeks, she was a vamp. Her vampiness might have been the result of Zeus forcing her to marry the god Hephaistos, who was lame, misshapen and mean. Since she had nothing in common with Hephaistos, and also didn’t take kindly to being forced to marry anyone, Aphrodite began going out with other guys….” In a more scholarly tone, she writes that “Jane Harrison thinks that before the Greeks demoted her into a sex goddess, Aphrodite was a goddess who just never married, a parthenogenetic deity who could create life without mating… – which of course suggests that originally she was a great goddess, the uncreated source that created everything.…” She goes on to discuss the goddesses Holda and Perchta, which in relation to Mother Goose she calls Holda-Perchta, and explains that they both had many other names depending on the time and location. She describes how these goddesses were “degraded” by those who were trying to stop Europeans from worshiping them, and then goes on to discuss the Grimms’ Fairytale, “Mother Holla,” giving Heide Gottner-Abendroth’s opinion of the tale and Marija Gimbutas’ opinion about Holda. Her exploration of the connections among Harlequinn, Hellequinn, Helle, and Holda are focused on “early modern” theater productions which show relationship among these and among Holda and what was called “The Wild Hunt, a supernatural group of mostly dead people that roamed the medieval medieval countryside in the dead of night.” Her investigation of “Mother Goose and the Graphic Arts” is an extraordinary example of scholarship that includes primary research. In the section on American portrayals of Mother Goose, in which she takes a close look at 18 Mother Goose images, she tells of trying to find the answer to the question of how Mother Goose came to be portrayed as “witch-like.” She finds the answer to this in a description of an 1806 theater production of a play by Thomas Dibdin and tries to figure out how to get a copy of the script. She discovers that such a copy is in the Harvard University library where “Harvard librarians weren’t letting it out of their hands.” She describes the way she finally got a copy of the document as a “miracle of miracles” and how, through it, she found even more information than the reason for the “witch-like” representation. Part Two of the book includes a close look at Mother Goose fairy tales including a list “of 12 characteristics that, taken together, set the fairytales apart from other fiction”; a look at the implications of “Cinderella” and other fairy tales and codes within them; and other fairy tales about “creation, cosmology and theology” as well as those about “magic spells and incantations.” In “Fairy Tales About Right and Wrong” she looks into the question of why there seems to be no portrayal of war in fairy tales and whether the violence that does exist in them “might be the result of patriarchal revisioning.” The last chapter of the book is titled “Questions, Questions and more Questions.” The back matter of the book includes appendices with “Frequently Used Terms and Time Periods,” “Mother Goose Timeline,” the text of “ Grimms Fairy Tale N0. 24, Mother Holle,” “Perrault’s Tales of Mother Goose: A Synopsis of Each Tale,” “Fairy Tale Code Words and Their Meanings (From Heide Gottner-Abendroth’s The Goddess and Her Heroes),” “Discussion Questions”; and a 16.5-page bibliography and 19-page index. The front matter of the book includes acknowledgments and notes about illustrations, including an explanation of why they aren't included in this book, along with information about a book and websites that can provides the reader with such illustrations. Breaking the Mother Goose Code is an important book, not only for its subject matter about Mother Goose, fairy tales, and Goddess mythology, but also for the examples it sets of ways to trace the history of Goddess suppression and of how to present this type of material in a scholarly yet very accessible way. I recommend it with great enthusiasm. Jeri Studebaker has worked on several archaeological sites and has advanced degrees in anthropology, archaeology, and education. She is also author of Switching to Goddess. ~ Judith Laura, http://medusacoils.blogspot.com/2015/07/review-jeri-studebakers-breaking-mother.html

Well researched, readable, thought-provoking By SAStirling on April 3, 2015 Format: Kindle Edition I was very keen to read Jeri Studebaker's Breaking the Mother Goose Code - How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years, partly because it looked interesting, and partly because my theatrical hero - Joey Grimaldi, King of Clowns - appeared in the first modern pantomime, Harlequin and Mother Goose; or, the Golden Egg, which did great business when it hit the stage at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, in December 1808. I wondered - just wondered - whether Jeri Studebaker might mention the Mother Goose pantomime in her book. And I was not disappointed. Jeri had done her homework. The first part of Breaking the Mother Goose Code really does focus on the character of Mother Goose, drawing attention to the similarities between this alternately beautiful and grotesque figure and certain ancient European mother-goddesses, especially Holda-Perchta. The second half takes the argument further, beyond Mother Goose herself, to examine the ways in which so-called "fairy tales" function as a kind of oral memory of the time when Goddess worship was widespread (and largely uncontested), and how these fairy tales - especially when shorn of their latter-day accretions - can be thought of as shamanic journeys and/or magical rituals and spells. The idea, overall, is that patriarchy is a fairly new phenomenon. And it's a stinker. Whenever and wherever it appears, it pursues a sort of scorched earth policy. But people - whole populaces - don't just alter everything they believe overnight because an angry man tells them to. Those pre-patriarchal belief systems were natural and hardwired into our collective psyche. In the face of barbaric violence and blanket intolerance, the old ways lived on - surreptitiously - and did so, partly, through the transmission of fairy tales. I like this idea. Mainstream history has been rather naughty, I feel, in taking such a dismissive and lofty attitude towards "folk" history (local legends, place-names, fairy tales). Just because these things weren't written down till a late stage, doesn't mean that they don't provide us with important glimpses of ancient knowledge. The Australian aboriginal sang the world back into existence with his song-lines, re-making the landscape by telling its stories, long before the White Man arrived to tell him he'd got it all wrong, and then make a slave of him. Jeri Studebaker's research for this book is ample and impressive. She really knows her subject and has gone into it in great depth, producing a book that is both readable and stimulating. Hard facts mingle with interesting theories and speculations. And nowhere, I feel, is Jeri at her best more than when she is taking a wrecking-ball to patriarchy. The differences between patriarchy (recent, bloody) and pre-patriarchal societies (been around for ever, generally equitable and non-violent) are brought out in such a way as to illustrate, not only what a disaster patriarchal structures have been for the species and the planet, but what we lost when we allowed our more natural societies to be steamrollered by the maniacs of patriarchal thinking. So many lives lost. So much wisdom lost. So much damage done. In fact, Studebaker doesn't belabour this point, but chooses her examples carefully, citing experts in these matters. Her argument - that fairy tales like Mother Goose represent a sort of quiet resistance, a continuation of pre-patriarchal values in a time of patriarchal thuggery - grows, little by little, from her near-forensic analysis of Mother Goose (Holda-Perchta) herself to the wider world of fairy tales and their magical methodology - until, in my case at least, I was convinced. Strip away the Disneyfication, and fairy tales really can take us back to a pre-patriarchal age of equality and possibilities. ~ Simon Stirling, Amazon.com

Review from Pagan Square (by Lia Hunter) Imagine... What if Mother Goose was the ancient European Mother Goddess in disguise, hidden from the patriarchal, monotheistic church that took over Europe, appearing in print just as the Inquisition and Witch-hunts drove anything non-Christian underground? What if the Mother Goose “nursery rhymes” taught to children over the last few centuries were a way to pass on an encoded pre-Christian worldview? Are fairy tales the carriers of the Pagan values of ancestors who had to disguise them as “peasant imbecilities” to keep them in cultural memory in a stratified society, of which the hierarchical authorities wanted to eradicate their egalitarian, animistic, and earthy worldview? These questions are explored in Jeri Studebaker’s new book, “Breaking the Mother Goose Code: How a Fairy-Tale Character Fooled the World for 300 Years” published by Moon Books. I was excited to read the advance copy I asked for, since folklore and fairy tales have always fascinated me, and I really love reading about history - especially Pagan history. I know I’m not alone in these interests, so I thought I’d share my thoughts on the book after reading it. Not only does the book address the specific history of the publishing of the Mother Goose tales (Charles Perrault, etc.) and the rhyme about Mother Goose, herself (Old Mother Goose When She Wanted To Wander) and the imagery in the illustrations over the centuries, but it explores the specific goddesses she resembles (Hulda/Helle/Hel, Aphrodite, the neolithic bird goddess…), and the symbolism surrounding her that matches with ancient mythology (spinning, the world egg, ducks/geese/swans…), and it looks into the tales and rhymes for what values and lessons might be encoded in them, and how they differ from the prevailing Christian cultural attitudes of the times. All of these aspects of the book were interesting in their own way. I could have read more about each subject, but I was also satisfied with the book-length presentation. There are even appendices in the back with a few relevant synopses of fairy tales, the full Grimm’s “Mother Holle” tale, and a set of discussion questions for reading the book with a group. One weakness in the presentation was the lack of illustrations. There was much talk of book covers and illustrations, analyzing their imagery, but I had to look them up myself on the Internet as I was reading about them. The book could have really used pictures if it was going to talk about specific images so much. I would hope there will be illustrations in future editions. Perhaps if the book does well, that will happen. It was a pleasant, transporting (to childhood, to ancient Europe, to the middle ages and more recent centuries), magical read, and I find myself hungry to go look up more about these symbols and goddesses and read even more fairy tales with an eye to what gems might be hidden within them, though I’ve long known there are lessons in them, having been a reader of the Journal of Mythic Arts’ Folkroots columns and Clarissa Pinkola Estes’ “Women Who Run With The Wolves.” Now I can look even deeper into time (before Indo-European patriarchy as well as pre-Christianity) and keep the Pagan ancestors in mind as I read the tales. I’ve also been collecting Mother Goose images on Pinterest, because now they’re full of meaning for me. As a Pagan, I feel grateful to the ancestors for preserving what they could and sending these messages to us through time. My fascination with fairy tales does seem to be what guided me onto the path I walk now. Magic and kindness and laughter and egalitarian values did seep into my soul from my immersion in the tales and rhymes I loved so much as a child. They also seem to have made it into the contemporary fantasy being written today, and that also helped me find my way back to where I belong. I’m also grateful to the scholar and author of this book, Jeri Studebaker, for reconnecting the dots so more of us can get the message and find our way back to our heritage, which had to be hidden during a long and brutal oppression. The time has come for the knowledge to blossom again, and for us to reclaim the cultural heritage of peace, equality, and joy that was suppressed. Have a gander (hehe) into this book if you'd like to do some reclaiming, or if you enjoy history and fairy tales. It may touch you as deeply as it did me. ~ Pagan Square, http://www.witchesandpagans.com/sagewoman-blogs/the-tangled-hedge/breaking-the-mother-goose-code.html

Fascinating By Yvonne on February 19, 2015 Format: Paperback This is a fascinating book involving detection, ancient practices, fairy tales, nursery rhymes, our ancestors and goddesses all based around the tale of Mother Goose. Basing her ideas around two main theories 1) that Mother Goose was a European goddess in disguise and 2) that Mother Goose appeared from nowhere at the time that European Pre Christians were being dealt a final blow with inquisitions and witch burnings, Studebaker sets out to prove that hidden within Mother Goose was in fact a goddess, a way of disguising the evidence until it was safe to reveal it. Holda-Perchta , Aphrodite and Brigid are amongst those considered to be the goddess depicted by Mother Goose. Painstaking research and a creative and delving mind are put to task in teasing out links however tenuous at first in order to support her hypothesis and then the wider field of the purpose of fairy tales. The author looks at the secrets that are hidden in nursery rhymes of the time and in the second part of the book, at other early or Pre-patriarchal fairy tales and the various theories over their purpose in society as well as their common characteristics and proposing her own 'secret code theory'. Finally, over several chapters she looks at specific European fairy tales and the information they provide about our goddess centred ancestors. I have no memory of the Mother Goose tale as set out in this book, nor have I more than a passing knowledge of goddesses, this however did nothing to lessen my interest, particularly in the second part of the book where I found myself totally caught up in the world of my ancestors as disguised in fairy tales. ~ Jeri, Amazon.com (US)

Almost a Terrific Book By Diana in Chicago on February 17, 2015 Format: Paperback Verified Purchase This well-researched book tracing (and speculating about) the origins of Mother Goose and the symbolism contained in these familiar tales and nursery rhymes is an impressive piece of literary detective work. Although scholarly, it is written in a warm, witty, conversational style, and is a highly enjoyable read--with one glaring omission that kept me from giving it five stars. Just a few pages into the book, the author refers to "mysterious statues found in certain old French churches. . . these puzzling statues have one human foot, but a second foot that is webbed--like the foot of a goose." I eagerly flipped through the next few pages, then the entire book, looking for pictures of the statues and quickly discovered there were none--in fact, THIS BOOK, WHICH FREQUENTLY CITES SPECIFIC ARTWORK AND CRIES OUT FOR ILLUSTRATIONS, CONTAINS NOT A SINGLE ONE! Instead, the reader is directed to several websites that offer related art, and an entire chapter is devoted to verbal descriptions of illustrations appearing in other books! I wound up doing a lot of Googling--with limited success--but never did find pictures of the goose-footed church statues. Still, this book contains a wealth of information and an excellent bibliography, and deserves a place in the library of anyone interested in folklore, literature, or mythology. ~ Diana, Amazon.com

The author is to be congratulated for giving us this brilliant and utterly absorbing work of detection, which traces in great detail how ancient beliefs and practises related to the Great Mother and Great Goddess of pre-patriarchal societies were incorporated into fairy-tales, folk-lore and even nursery rhymes. A wonderful, informative book opening the door onto the hidden meaning concealed in many of these treasures that have fortunately survived to our time. ~ Anne Baring, Jungian analyst, lecturer, and author of several books including The Dream of the Cosmos: A Quest for the Soul.

I am normally a silent reader, not one who leaps into the air, fist clenched, shouting "YES!" every now and again. My unusual cheerleading behaviour was entirely due to the fact that I was so happy to read a book about goddess that actually proposes some real, radical solutions to the mess our world is in right now…. The greatest thing about the book is - quite apart from the fact that it might help to save the planet and us all - is its readability and the feeling of breathless adventure I got from it.... ~ Geraldine Charles, Editor, Goddess Pages

Review of previous book Switching to Goddess: The author makes a strong case for switching to Goddess as a viable option for restoring a balance in our social lives, a balance that once existed in the Neolithic oecumene or commonwealth, a model of society based on the principle of socioeconomic egalitarianism.... ~ Dr. Harald Haarmann, culture historian, internationally-known linguist

A hard-hitting get-up-and-go book that challenges the reader with its racy style and punchy arguments. Backed up by scholarship, it is a clarion call for our times. ~ Claire Hamilton, author of Maiden, Mother, Crone, and Tales of the Celtic Bards.