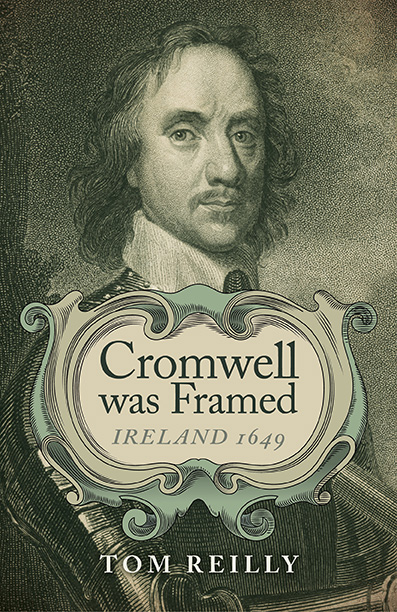

Cromwell was Framed

Revealed: The definitive research that proves the Irish nation owes Oliver Cromwell a huge posthumous apology for wrongly convicting him of civilian atrocities in 1649.

Revealed: The definitive research that proves the Irish nation owes Oliver Cromwell a huge posthumous apology for wrongly convicting him of civilian atrocities in 1649.

Revealed: The definitive research that proves the Irish nation owes Oliver Cromwell a huge posthumous apology for wrongly convicting him of civilian atrocities in 1649.

Great britain, Ireland, Social history

The publication of Tom Reilly’s book "Cromwell: An Honourable Enemy" fifteen years ago sparked off a storm of controversy. Many historians publically derided the divisive and ground-breaking study. Dissatisfied with the counter-explanations of these experts on Cromwell’s complicity in war crimes in Ireland, amateur historian Tom Reilly again throws down the gauntlet to professional historians everywhere. This book contains original and radical insights.

Breaking the mould of the genre, for the first time ever, Reilly publishes the contemporary documents (usually the preserve of historians) so that the authentic primary source documents can be interpreted by the general reader, without prejudice. Among the author’s fresh discoveries is the revelation of the identity of two unscrupulous individuals who created the myth that Cromwell deliberately killed unarmed men, women and children at both Drogheda and Wexford, and that a 1649 London newspaper reported that Cromwell’s penis had been shot off at Drogheda.

Whatever your view on Cromwell, this book is persuasive. Conventional wisdom is challenged. Lingering myths are finally dispelled.

Click on the circles below to see more reviews

Book Review: Was Cromwell Framed? John_Dorney 26 September, 2014 Reviews Cromwell was Framed, Ireland 1649 By Tom Reilly Published by Chronos Books, London, 2014 Reviewer: John Dorney Oliver Cromwell’s name is one the most potent symbols in Irish historical memory. The mere mention of it generally prompts such epithets ‘as ‘murderer’, ‘scumbag’, ‘genocidal maniac’ and so forth. So infamous has the memory of his campaign in Ireland from 1649 to 1650 become. Tom Reilly contributed an engaging summary of his book to the Irish Story recently, reiterating his argument, first penned in his 1999 book, ‘Cromwell, an Honourable Enemy’ that Cromwell was in fact not guilty of the charges of the mass murder of Irish civilians of which he is accused. In this book he defends this thesis against various historians who have criticised it, notably Michael O Siochru in ‘God’s Executioner’. Reilly argues that Cromwell was in fact not guilty of the charges of the mass murder of Irish civilians of which he is accused. The format of ‘Cromwell was Framed’ is not as readable ‘An Honourable Enemy’, as the former consists in large part of lengthy reprinting of contemporary sources, in an effort, says Reilly, to let the reader make their mind up for themselves. This is indeed interesting in places; Cromwell full address to the Irish Catholic Bishops for instance is fascinating. Take this stirring piece of invective penned by Old Ironsides; ‘remember ye hypocrites that Ireland was once united to England. Englishmen had good inheritances which many of them purchased with their money…they lived peaceably and honestly among you…You broke this union. You unprovoked put the English to the most unheard of and barbarous massacre (without respect to age or sex) that the world ever beheld. And at a time when Ireland was at perfect peace and when through the example of English industry through commerce and traffic, that which was in the natives’ hands was better to them than if all Ireland had been in their hands and not an Englishman in it.’ Cromwell goes on to explain why put puts the fault for the war in Ireland squarely on the shoulders of the Catholic clergy who have duped their ‘poor deluded laity’ and who use the ‘fig leaf’ of support for the King to further their designs for religious domination. ‘We are come to break the power of a company of lawless rebels, who having cast off the authority of England, live as enemies to human society’. But elsewhere the reader can flag a little at the relentless detail of the arguments over what Cromwell did and did not do, specifically at the siege of Tom Reilly’s native Drogheda in 1641. Reilly argues that far from being a slaughterer of civilians, Cromwell respected the laws of war (such as they were at the time) during his campaign in Ireland and did his best to protect civilians. He argues that in the siege of Drogheda there is no compelling evidence to show that any large number of civilians were killed and that at Wexford the following month those civilians who died accidentally drowned while trying to escape or were killed in the crossfire between the two sides. So for the reviewer there are two questions. One, is he convincing? And two; does it matter? Drogheda – A Civilian massacre? Let’s deal with the first question first – did Cromwell massacre the inhabitants of Drogheda in September 1649? As we have covered here on The Irish Story before, on September 11 of that year, Cromwell, leading the English Parliamentarian New Model Army summoned the garrison of Drogheda to surrender. Drogheda was held by a Royalist force with both English and Irish troops led by the English Catholic Arthur Aston. Aston would not surrender and the town was stormed. While the slaughter of Royalist soldiers at Drogheda was horrific, there is little evidence that large numbers of civilians were killed there. Almost the entire garrison of 3,000 men, including Aston himself, was killed, many after they had tried to surrender and some after they actually did surrender. The heads of the Royalist officers were, in manner reminiscent of contemporary atrocities in Syria and Iraq, cut off and put on poles along the road back to Dublin. Whether or not one accepts, as Reilly does, that this was within the accepted boundaries of 17th century warfare, it was still a horrific event. Only by retrospective dehumanisation of the Royalist soldiers can this be denied. However this is not the core of the book’s argument. Royalist and Irish Catholic writers and propagandists in the months and years afterwards maintained that Cromwell’s troops massacred the unarmed townspeople of Drogheda. Is this true? Reilly argues cogently that it is not. To a large extent it appears he is right. There are very few references to civilians being killed wholesale during the siege in contemporary accounts and only a few of accidental or what we might call ‘collateral’ killings. The exception to this is Cromwell’s own letter to Parliament about the siege. It listed 2,800 Royalist soldiers killed ‘and many inhabitants’. Reilly points out that the original of his letter does not survive and that some reproductions of the letter contain the line about civilians and some do not. Moreover Cromwell himself vociferously denied later that year at New Ross that he had ‘killed, massacred or banished’ anyone who was not ‘in arms’ in Ireland. Moreover as Reilly points out, Drogheda had been consistently in Parliamentarian hands from 1647 to 49. There was no automatic reason why the population should have been targeted for massacre. In the opinion of this reviewer, we therefore cannot be sure that a massacre of civilians (as opposed to surrendering soldiers) occurred at Drogheda and we should really stop saying it did. It is certainly possible that civilians were killed in the sack, maybe even several hundred, but it seems clear there was no targeted massacre. We can also note that at the sieges of Kilkenny and Clonmel, where his assaults were repulsed with heavy losses (in the case of the latter grievous ones), Cromwell fully respected the terms of surrender he agreed with the Irish Catholic garrisons there and the townspeople. At the very least the picture of Cromwell as indiscriminate killer must be modified. Cromwell’s significance in Irish history On to question two; does it matter? The thesis here seems to be, to paraphrase; ‘in 1649 English Parliamentarians killed English Royalists at Drogheda as part of a civil war throughout these islands and Irish nationalists mistakenly remember it as an example of English tyranny in Ireland’. This is where I felt the book’s argument was much weaker. At the very least this hugely oversimplifies events in mid 17th century Ireland. In particular the thesis that since Drogheda had been a Pale (i.e. English speaking) town in the medieval period it would not have been Irish or Catholic in 1649 is very much mistaken. Irish identity was in flux at the time, being forged on the anvil of religious war. In 1641 Gaelic Irish rebels from Ulster came to the Pale around Dublin and for the first time in history the English speaking Pale lords, in a famous ceremony at the Hill of Crofty in County Meath declared common cause with them as fellow Catholics. Where this book is weaker is in setting the historical context of the Cromwellian campaign and its significance. Tom Reilly’s assertion here that the Pale rejected the uprising of 1641 is plain wrong. When Drogheda was besieged for first time in 1641 elements of the town’s population attempted to open the gates for Phelim O’Neill’s insurgents. Similarly his idea that Dublin supported the Parliamentary forces on principle seems to downplay the fact that the Catholic population had actually been expelled from the city during the wars after 1641. He sets up a distinction between the townspeople of Drogheda (English) and Wexford (Irish) that would have seemed odd at the time. Both were predominantly English-speaking Catholic towns. That Wexford was held by Irish Confederates and Drogheda by predominantly English troops (first Royalists and then Parliamentarians, then Royalists again) was simply the fortunes of war. A generation earlier both towns would have been deeply hostile to their Irish speaking Gaelic neighbours in the Nine Years War. But by the 1640s, for better or for worse, it was principally religion that determined people’s allegiances. The idea that a new Irish identity was formed out of Catholicism and loyalty to the English King, Charles Stuart against the English Parliament is not that many Irish people would identify with today. But not to appreciate this and not to appreciate that resisting Parliamentarian conquest for Irish Catholics meant, as they saw it, resisting dispossession and religious persecution is to fail to recognise why Cromwell became a hate figure in Irish popular understanding. The war in Ireland from 1641-52 was incredibly fractious and complex. For most of the 1640s the Catholics, organised in the Confederate Catholic Association, based in Kilkenny, fought with Parliament- backed Protestant forces and negotiated with Royalist ones for a possible settlement. It was only in 1648 that they joined a pan Royalist alliance aimed at defending Ireland from Parliamentarian invasion (and not without factional fighting in their own ranks over this alliance). Losing Drogheda, therefore an important port for resupply, to the most anti-Catholic faction of the Civil Wars – the New Model Army – would indeed have been a devastating blow to politically aware Irish Catholics. It was not an irrelevant squabble between English factions. What was more, Cromwell’s campaign of 1649-50, seizing most of the walled towns in eastern Ireland paved the way for the subsequent incredibly brutal guerrilla war, in which large parts of the country were devastated by Parliamentarian forces. We might conclude, as Reilly does with some reason, that Cromwell himself did not massacre civilians in Ireland, but we cannot say the same of his successor commanders, Henry Ireton, Charles Fleetwood and Edmund Ludlow. The death toll from their scorched earth tactics in the subsequent years certainly reached into the hundreds of thousands. Furthermore under the Commonwealth regime, the ownership of the land of Ireland passed almost in its entirety to Protestant settlers, a fact that determined perhaps the next two hundred years of Irish history. If Cromwell became a demon figure in Irish folklore it was not necessarily a result of what he did or did not do at Drogheda but because he personally stood in for an immensely traumatic period in popular memory. And yet as Tom Reilly would no doubt point out, none of this changes the fact that there is very little conclusive evidence of a civilian massacre at Drogheda. In this limited sense, Cromwell was indeed perhaps ‘framed’. ~ John Dorney, The Irish Story

While the book is to be recommended for Mr By michael g.floyd on August 10, 2014 Format: Paperback While the book is to be recommended for Mr.Reilly's research and his inclusion of copies of original documents his anti-Catholic views, as promoted in a previous publication "Hollow be thy name" casts him as a not totally unbiased writer. He cites ancient superstition as the fault of the Church. Cromwell was anti-Catholic and anti-Papacy and it appears he has a fan in Mr.Reilly on many levels. Less personal opinion. The facts please, stick to the facts. Religion has caused enough problems. ~ Michael G Floyd, Amazon

Most Helpful Customer Reviews 4.0 out of 5 stars A Different And Engaging View of Cromwell 11 July 2014 By Shonda Slaughter Wilson Format:Paperback Tom Reilly discusses Oliver Cromwell's role in Ireland with a fresh and different perspective. His take on Cromwell, although very different from that of many historians, argues that Cromwell, despite contemporary claims, played a less violent role in the Ireland campaign and many atrocities attributed to him (specifically in Drogheda and Wexford in 1649). Reilly's language is engaging and entertaining and his argument has merit, it got my attention and raised questions regarding modern concepts of Cromwell in Ireland. While Reilly and I did not always agree and I raised issue with his use of sources, I found the book very interesting and recommend it to anyone interested in the subject. You can really tell Reilly is passionate about his work, deeply immersed in the world of Cromwell and he wants the rest of the world to look at Cromwell in a different light. I think Reilly adds something to the ongoing historical discussion and raises questions about source validity that should be looked at and I learned from reading his book that although you may not always agree with an author's argument...it is important to get a wide spectrum of perspectives on an issue and Reilly offers one of many. Luckily, because I reviewed the book for another site (a much more in depth review that I will not repeat here), I had the amazing opportunity to discuss Reilly's book with him and he offered a constructive discussion to my problems with the text and I found that quite refreshing. Reilly writes a book for everyone to read and I believe truly wants his readers to simply attempt to look at Cromwell in a different light. ~ Shonda Wilson, Amazon

A Brave Man Tries to Lift the Curse of Cromwell CROMWELL WAS FRAMED By Tom Reilly Chronos Books €18.99 approx IF EVER there was another brave man and a contrarian to boot, it is Tom Reilly. He has gone in the face of at least 300 years of opinion in his efforts to rehabilitate the reputation of the great bogeyman of Irish history. I heard the name Cromwell long before I ever knew who he was. In moments of rare anger, usually at some machine that refused to function as it should, my father would mutter “The curse of Crummell on it.” At least that’s what I heard. I even thought Crummell was some pagan god, like Lugh or Manannan Mac Lir. It took a long time for the penny to drop that the curse was that of Cromwell. Ask any English person to quote Cromwell, and the likely answer will be “Paint me, warts and all.” Ask the same question of an Irish person, and they will instantly reply “To hell or to Connacht”. There stands illustrated the difference in perception: in England Oliver Cromwell was a great republican, unconcerned with courtly appearance. In Ireland he is Hitler, Stalin, Mao and Pol Pot rolled into one. The Irish town with which Cromwell’s name is inextricably linked is Drogheda. He is reputed to have massacred the inhabitants of the town, men, women and children, when his New Model Army besieged and captured it from the Royalists in 1649, during the Irish phase of the English Civil War. Tom Reilly is from Drogheda, and in 1999 he published his first book, Cromwell, an Honourable Enemy. This was the 350th anniversary of the fall of Drogheda and the book got a largely hostile reception. It was unfortunate for Reilly’s thesis that he had no academic qualifications in history — he admits that he failed it in the Leaving Cert. So the critics who bothered to review his book dismissed it because of its lack of academic technique and its faults of interpretation. However, in this new work, Reilly sets out the sources of his argument and actually reproduces many of them in facsimile. Essentially what he says is that Cromwell’s men did kill a large number of people in Drogheda, but that these were the defending soldiers. It would be regarded as a war crime now, but in the 17th century there was a protocol when it came to sieges. The attacking army arrived under a white flag of peace and offered terms of surrender, the minimum of which was that the defenders could leave with their lives. It was worthwhile for the attackers to do this: a long siege could do more damage to the besiegers, living in the open, than to the defenders, cosy in their homes or barracks except during actual assaults. If the defenders refused terms, then the red flag was raised, and in theory this meant no quarter would be given. In fact, quarter was often granted after the initial attack had succeeded and subsided, but there were usually some executions, often of the commanders. Reilly acknowledges that upwards of 3,000 soldiers were killed at Drogheda, but he maintains that the civilian population had left the town before the siege, and cites Corporation records from before and after the siege of 1649 showing that prominent citizens of the town were still alive and active in civil affairs long after the Roundheads had gone. His arguments are persuasive and he does not make Cromwell out to be an angel. He disliked the Irish and he detested Catholicism. But, says Reilly, he was not a war criminal, merely a commander of his time. Read his book for yourself, and continue the argument. As the author says, only history can be the winner. ~ David Burke, The Tuam Herald

Cromwell Was Framed: Ireland 1649 By: Tom Reilly Chronos Books Review Written by: Shonda Wilson There are moments when as a reader, one just wants a book to be good for a variety of personal reasons. Perhaps the author is a favorite or the subject, but either way, the reader picks up the book with a preset desire for an enjoyable reading experience and sadly sometimes that ends in disappointment. This feeling of disappointment occurs frequently for historians when attempting to read what academics call “popular history,” or books written about history, but not by traditionally educated historians. Now, not all popular histories are bad and dozens of popular historians get it right producing well written, documented, and thought out texts on popular historic events and even the most educated historian enjoys those books, regardless of the author’s education. Personally, when I have free time, I love reading books by Sarah Vowell, John Meacham, and Barbara Tuchman all popular historians and each producing high quality, researched, and expertly written texts. Moreover, I am still learning myself and as a mere grad student working towards the coveted PhD, I tend to give these authors a little leeway if the book is geared towards the wider public audience and slated to sell in the major box bookstore market and not merely to academics and experts on a subject (I read mostly those books and they are for two very different types of people). That being said, books written about the past and authors who make specific and controversial arguments in those books have a responsibility to prove what they say and produce a paper trail or evidence to support those arguments and unfortunately that is where myself and author Tom Reilly have issue. Reilly’s latest book, “Cromwell Was Framed: Ireland 1649” boldly claims that centuries of well trained historians get Cromwell and his intentions in Ireland during the seventeenth century wrong. That claim in itself is not outlandish or new, historians bicker constantly over the most minute of details throughout history, but where Reilly and other historians making such claims differ is in proving their case. “Cromwell Was Framed” mentions documents, letters, and events contemporary to Cromwell’s experiences in Ireland during 1649, but provides little contextual documentation or footnotes regarding said references. The lack of contextual reference seriously threatens the plausibility of his claims. Furthermore, the documents and evidence Reilly often uses to prove his point comes from questionable sources (can we really trust a public statement by Cromwell himself disavowing any desire for violence against the Irish people or believe Reilly without proof that all contemporary published works accusing Cromwell of violent atrocities in Drogheda and Wexford were highly over exaggerated or fabricated). Finally, Reilly has a tendency to argue with historians who panned his first book and lash out at Catholics and his obvious animosity often creeps in, causing disruptions in the flow throughout the text, which left me feeling like a person stuck in an awkward conversation where one friend constantly talks badly about the other. Essentially, I struggled with “Cromwell Was Framed”and often found myself pushing through the book without a desire to go further. Reilly lost me early on and while his writing is fluid, conversational, entertaining, and accessible to a wide audience (vitally important in popular history), his argument never fully solidified and I found it hard to believe because Reilly gave me no concrete proof. As I stated before, although Reilly includes portions of documents and personal letters to support his argument, without source information or context, it is very difficult to determine authenticity. Tom Reilly likes Oliver Cromwell and uses his book to consistently excuse Cromwell’s violent military actions throughout Ireland citing Cromwell’s right of military conquest when one town refuses to surrender or making semantics arguments in regards to public statements that referred to massacres of men, women, and children (he claims document wording has been misunderstood to and massacres overstated). When the author fails to excuse Cromwell’s behavior, he shifts responsibility, often placing blame historical misinterpretation, a conspiratorial contemporary press (who often all met together at the same place to formulate their lies), and the Catholic Church (he does this often). For example, early on in the text, after including a very large document Reilly uses to argue Cromwell’s issues with Ireland resided with the Catholic Church and not the Irish population (something quite hard to separate when one considers the percentage of Irish Catholics in the seventeenth century), he states plainly, “It was the Catholic clergy that was the source of Ireland’s woes and it was they with whom he had major issues, not the people of Ireland.” I do understand how, from Cromwell only, Reilly makes the claims he does in the text, but without a comprehensive look at all sides of the argument and adding to those claims an obvious bias, the lack of reference again creeps in as a hinderance to Reilly’s argument. Moreover, if Reilly offered solid proof of a conspiracy against Cromwell in the press, some evidence that the contemporary poems and stories referencing the massacres in Ireland were false, I would love to see it and I believe the inclusion of such proof would drastically improve the validity of Reilly’s argument. Without such, as a reader, I found it very hard to agree with Reilly’s claims and often agreeing with the historians he refuted in the text who cited Cromwell’s own denial of ill intentions as a strategic military and political move. When I picked up Reilly’s book, I wanted to immerse myself in his alternate view of one of history’s famed villains. Despite his lack of academic background, I opened my mind and readied myself to take his thesis seriously, look at his evidence, and consider the idea that perhaps other historians mistakenly blamed Cromwell for atrocities that (as Reilly claimed) did not exactly sit well with the subject’s personality, but Reilly’s argument never solidified for me. In other words, I wanted to give Reilly and Cromwell a chance and believe him when he (Cromwell) said: “I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible that you might be mistaken.” The documents Reilly did include to supplement his own claims were highly interpretive (the author himself acknowledges this) and he offers no context or reference to said documents apart from copying and pasting them into his book (sometimes in their complete form, but again without context). Furthermore, every chapter in the text includes Reilly’s obvious issue with the negative criticism he received from his earlier work and this proves to be disruptive to the issue at hand (Cromwell’s behaviors in Ireland). “Cromwell Was Framed” read well, I enjoyed the author’s ideas and wanted to give them a chance, but the fractured nature of the text and the lack of contextual documentation and solid proof often left me questioning his conclusions. Reilly’s book had good points and great ideas, but without the solid evidence, I struggled as a reader to believe his argument. To be perfectly honest, if Reilly tweaked his text slightly by offering extensive notes on his sources, provided contextual resources on said sources, and cut out his arguments against historians who disliked his first book, I believe my issues with “Cromwell Was Framed” would dissipate. With that in mind, I am going to recommend those interested in Oliver Cromwell read “Cromwell Was Framed.” While I personally believe that Reilly lacked concrete evidence, I found the book entertaining, highly readable, and his argument compelling due to its very different take on the actions and personality of a man often depicted as a “bad guy.” ~ Shonda Wilson, A Bibliophile's Reverie

3.0 out of 5 stars A Gutsy Historian! 1 Aug 2014 By Chris Fogarty - Published on Amazon.com Format:Paperback Bravo to Tom Reilly, for digging deeper than professional historiographers! In this book he provides evidence suggesting that monarchists then, and nationalists more recently, have been wrong in accusing republican Cromwell of a massacre of non-combatants at Drogheda in 1649. Three crucial words are involved; "...and many inhabitants." Did Cromwell's troops kill them, also? Reilly claims "No" on the basis that those three words are absent from other key documents and were probably inserted by monarchists. This engagingly-written book includes details of Cromwell's destruction of Catholic churches, of his decision to storm a town rather than accept its surrender contingent upon allowing its inhabitants free exercise of their Catholicism, of his ethnic cleansing of Ireland east of the Shannon ("to Hell or Connacht"), and of his shipping of innocents to slavery in "the Tobacco Islands," etc. Despite the genocidal policies of Britain's State Church in Ireland at the time, this book attacks one religion; Catholicism. On page 46 the author states; "It was the Catholic clergy that was the source of Ireland's woes and it was they with whom he (Cromwell) had major issues, not the people of Ireland." As to Cromwell's pious platitudes of coming to save the people of Ireland the author approvingly writes (also page 46) "...there is absolutely no good reason to believe he was lying." So Author Reilly, having cast substantial doubt whether Cromwell oversaw the killing of Drogheda's noncombatant inhabitants, he extrapolates that reasonable exculpation into a strange claim that Cromwell is also innocent of all of his other crimes detailed in this book. This book contrasts sharply with perhaps the only other hagiographic portrayal of Cromwell; "Life of Cromwell," by J.T. Headley (1848). Though Headley's admiration of Cromwell exceeds Reilly's, and he matches Reilly's expressed hatred of Catholicism, Headley defends Cromwell, not by attempting, like Reilly, to exonerate him, but for being no more murderous to the Irish than Britain's monarchs; as follows; (Headley's page 302): "The truth is, Ireland has ever been regarded as so much common plunder by England. From the twelfth century till now, she has, with scarcely one protracted interval, suffered under the yoke of her haughty mistress; and it is not just to select out one period (Cromwellian) in order to stab republicanism. We have read history of modern civilization pretty thoroughly, and yet, we know of no examples of violated faith, broken treaties, corruption, bribery, violence, and oppression, compared to those which the history of the English and Irish connexion presents." "If the Commonwealth had lasted, Ireland would have been a Protestant kingdom and her subsequent misfortunes avoided." So, three stars for "Cromwell was Framed;" all three for the author's willingness to dig and to expose academic slackness. ~ Christopher Fogarty, Amazon

Do we owe Old Ironsides an apology?: Cromwell Was Framed – Ireland 1649 Review: Tom Reilly’s style is accessible and lively, but hero worship rather skews historical judgment Pádraig Lenihan Book Review Sat, Sep 13, 2014, 01:00 First published: Sat, Sep 13, 2014, 01:00 This is an angry little book. Tom Reilly lambastes three academics –John Morrill of Cambridge, Micheál Ó Siochrú of Trinity College Dublin and Jason McElligott of Marsh’s Library – because they panned his Cromwell: An Honourable Enemy (1999) out of “vested historical interests”. Cromwell Was Framed sets out an apparently more nuanced version of Reilly’s original assertion: large numbers of innocent civilians were not deliberately killed at the storming of Drogheda and Wexford in 1649. Reilly’s style is accessible and lively, but hero worship rather skews historical judgment, specifically in his choice of what evidence to accept and how to interpret that evidence. Reilly fully accepts only eyewitness accounts of what happened at Drogheda and Wexford published shortly after the events they describe. This blanket ban privileges accounts emanating from the winners, as competing narratives took longer and more circuitous routes into print. Reilly boasts, for example, that in Cromwell: An Honourable Enemy he already demolished a shockingly graphic account by a perpetrator of how he and his comrades killed women and children at St Peter’s Church in Drogheda. In fact Reilly’s critique betrayed an inadequate grasp of contemporary idiom and context. A “most handsome virgin” was “arrayed in costly and gorgeous apparel”, the perpetrator said. How, scoffed Reilly, could the soldier tell she was a virgin? Was it not ridiculous to suppose she would dress up and carry jewels in such dire circumstances? (The author can get it badly wrong when he tries to set a context. To take just one example: the “entire Pale community” did not face off against the native Irish in the 1641 rising. Had the Palesmen done so, the insurrection would have been a short-lived affair.) Reilly now relies essentially on the grounds that the confession did not find its way into print for over a century and the perpetrator’s brother, who wrote the account, may have been a closet Catholic. Disputed slaughter Indeed, accounts by Catholics, especially clergymen, are to be distrusted because their motives “could only have been disreputable”. Eight months after Wexford the archbishop of Dublin wrote that “many priests, some regular clergy” – other clerical sources name seven Franciscans and gives details of their deaths – “a great many citizens and two thousand soldiers were slaughtered”. Here is a clear unadorned and contemporaneous statement that noncombatants were killed: Reilly ignores it. Reilly is rightly sceptical of a post-Restoration petition from “ancient natives” of Wexford but seems, unjustifiably, to omit a statement by the bishop of Ferns, who recalled that English soldiers “murdered” three servants and a chaplain in his palace. Royalist news books are described as scurrilous – and, to be fair, often are. John Crouch’s The Man in the Moon includes the doggerel “For Noll (alack and alas for wo) / Has lost Lust’s Instrument / Which Makes his Wife to wail and sob.” I am not sure why Reilly includes a report that Cromwell had his penis shot off at Drogheda. But I am glad he did. Incidentally, Crouch and John Wharton are the two royalist hacks who “framed” Cromwell. Tom Reilly strains too hard to deflect blame from Cromwell in reading each document he does include. Each reading is, in isolation, credible, but the unrelenting cumulative effect is one of special pleading. Consider the three words at the end of a list of the dead at Drogheda appended to Cromwell’s letter of September 27th from Drogheda: “Two thousand Five Hundred Foot Soldiers, besides Staff-Officers, Chyrurgeons, & c. and many inhabitants”. On the basis of stylistic differences, Reilly insists that “it’s impossible to conclude” that Cromwell “definitely” wrote the appendix. Semantically, he has a point, but so what? If not written by Cromwell, the appendix was written by a secretary or officer and forms part of a single officially sanctioned publication associated with him and not repudiated by him. Armed civilians There is no dispute that it is Cromwell who admitted that “many inhabitants” of Wexford were “killed in the storm”, but Reilly insinuates the claim that the “inhabitants” of Wexford and indeed Drogheda (like the 70-year-old alderman Mortimer) “could have” been armed civilians. Almost anything “could have been”: Reilly does not supply positive proof that either or both towns raised trained bands to reinforce the defence. Hugh Peters, Cromwell’s chaplain and war correspondent, exulted in 3,552 “of the enemies slain” at Drogheda. If one subtracts 2,500 “foot soldiers” from 3,552, one is left with perhaps 1,000 massacred “inhabitants”. Reilly is having none of it: Peters “says nothing of inhabitants or civilians. The enemy were the enemy.” Would that it were so simple and that writers like this fiery cleric never used collective terms like “enemy”, “rebel” or “rogue” loosely. The definitive study of these events was written by James Burke more than 20 years ago, and academic scholars have moved on to other questions. Was Cromwell responsible for dragging out the war of conquest, with its cataclysmic human cost, by offering unattractive peace terms? Can more radical subordinates be blamed for a harsh postwar land settlement? I question the common assumption (not just by Reilly) that it was entirely acceptable to slaughter soldiers who surrendered without securing a promise to spare their lives during a storm. James Turner, a Scottish veteran of the Thirty Years War considered this “cruel inhumanity”. The royalist commander Ormond preened himself for sparing the lives of parliamentary troops taken at Baggotrath Castle (modern Baggot Street perpetuates the name) just a few months before the sack of Drogheda. That said, the following year another royalist commander, the Catholic bishop Éimhear Mac Mahon, slaughtered the English garrison of Dungiven. Practice varied. The author is to be commended for highlighting a subject that academic historians neglect but piques public interest: the publisher of Cromwell Was Framed asserts on its website that “the Irish nation owes Oliver Cromwell a huge posthumous apology for wrongly convicting him of civilian atrocities”. They shouldn’t hold their breath. ~ Padraig Lenehan, The Irish Times

Cromwell Was Framed – by Tom Reilly THIS BOOK is a follow up from Mr Reilly’s publication of Cromwell: An Honourable Enemy which was published 15 years ago. The original book created a huge controversy because with all that has been written by historians there was no way history could have been wrong … or could it? The book is full of point and counter points on what happened during those dark days in Drogheda and Wexford in 1649 Ireland. In this newest work Mr Reilly takes head-on his critics (professional historians) everywhere to dispute that Cromwell was the Devil incarnate as history would have us believe. We are presented with actual documents from those times – be they letters, newspaper articles, military accounts, etc of what was taking place during the various raids. In some of those accounts it seems that some of those fighting could not identify who was who – so there may well have been people killed by what we call today “friendly fire”. We must rely more on parliamentary statements (which, of course, as we all know, politicians are always forthright and truthful…) as there are no diaries or journals left by the residents of that time. Mr Reilly is certainly not trying to say that Mr Cromwell was an angel by any means, he is just trying to point out that perhaps he did not do all of the horrible things history accuses him of. There is no arguing that he has done due diligence to collecting information – I never realized there was so much available in documentation from that time period. He creates many new questions and casts doubt on many accounts. As I was educated in America I do not have any recollection of reading about this in the history books but I have heard about it from my extensive family in the UK. I’m not sure what to believe at this point but I always try to keep an open mind about things. Mr Reilly has done an excellent job of laying out the facts as much as possible and I would hope that you can draw your own conclusions (whatever they may be) in a more educated manner from this text. I am sure that mistakes were made on both sides during the battle and again, it was war and, as we well know, horrible things happen so it’s easy to look back on things and pick them apart but this definitely presents an eye opening view of things. It’s a good read, a bit hard to stick with at times if you are not a history fan but if you are interested in this slice of history then I highly recommend it. Read it and come to your own conclusions – or perhaps you have more questions? ~ Patty Smith, Union Jack Newspaper

Tom Reilly takes to task the perception that Cromwell was villainy personified Cromwell was Framed: Ireland 1649 by Tom Reilly, Chronos, £14.99 Buy here Of Oliver Cromwell, Ireland’s pre-eminent historian Roy Foster once wrote: “Few men’s footprints have been so deeply imprinted upon Irish history and historiography.” It could be added, too, that no historical character has come to personify more English misrule and callousness in Ireland, not least within the nationalist narrative. So it would take a brave soul to take to task the perception that Cromwell was villainy personified. It would be even braver for an Irishman to do so, let alone a native of Drogheda. But this has been the ambition of amateur historian Tom Reilly, who hails from the town that lives on in infamy, in which 3,000 men, women and children were butchered in 1649 at the behest of the future Lord Protector. The fable of Drogheda, Reilly maintains, was created by Cromwell’s enemy propagandists seeking to “bind the various confederate/royalist factions together” and has been regurgitated over the centuries by Irish nationalists and republicans, and by the Church, each for their own means. Reilly dismisses the “non-primary, post-Restoration” sources of Church historians, with their “disreputable” motives and “baseless allegations”. “To me, Cromwell was framed and I believe that this book proves it,” the author declares. “Therefore, I have a moral obligation, indeed I am duty-bound by history, to play my part in an attempt to overturn one of the greatest historical miscarriages of justice ever.” Although the author concedes it likely that parliamentary forces would have killed, and probably did kill, armed civilians, “no primary document whatsoever exists that provides details of the deaths of persons not at arms”. As a consequence, “we, the Irish nation, owe Cromwell an apology for destroying his reputation over the last 365 years”. Reilly finds no recorded incident of strife between the military and civilian occupants of Drogheda in the two years preceding the 1649 slaughter. Rather, the New Model Army enjoyed “cordial relations with the civilian population of Drogheda”. He also notes that, while in 1641 there were 3,000 people living in the town, in 1659 that number had risen to 3,500. “If the civilian inhabitants had been practically wiped out, it is very unlikely that within a 10 year period the town’s population would have replenished itself.” When Cromwell arrived in Ringsend, Co Dublin, on July 15 1649, he was “warmly welcomed by both the civilian and military populations of Dublin”. Cromwell was a fair fellow who had nothing against the Irish as a nation. On the contrary, on the march to Drogheda, when he discovered two of his men had stolen hens from an old woman, he had them hanged. “As for the people,” Cromwell once wrote, “what thoughts they have in matters of religion in their own breasts I cannot reach; but think it my duty, if they walk honestly and peaceably, not to cause them in the least to suffer for the same.” Nonetheless, Cromwell was a foe of the Catholic clergy, whom he blamed for stirring the impressionable natives into insurgency in 1641. It was the Catholic Church that was to blame for the “horrid massacres”, as Cromwell put it, of that year. The author has certainly received much attention from compatriots over the years for his attempts to rehabilitate Cromwell. Yet his revisionism would have been even more contentious, say, 50 years ago, when the nationalist narrative and the Church were mostly immune to criticism. Indeed, his invective against the Catholic Church is far from daring. It’s quite in keeping with the anti-clerical mood that has become voguish in the past 20 years in Ireland. It’s true that history is always moulded and distorted for contemporary purposes, not least in Ireland. And it’s always valuable – imperative, even – to question orthodoxies, as Reilly has sought to do. Yet his demographic study of Drogheda is dubious. In 1641, as he himself admits, Catholics outnumbered Protestants by five to one. In 1659, the undiminished population of the town was mostly Protestant. One can only assume that some ethnic cleansing and re-settlement occurred. Cromwell was Framed can at times be tedious, pedantic and self-regarding, with much of it written in the first person. Reilly is also over-indulgent on his subject who, he concludes, “was tender towards children … a family man who had a high moral threshold … acutely aware of the folly that such action would be dastardly deeds that he clearly abhorred”. Such an obsequious assessment of a man who “only” hated Catholics and killed armed civilians sails close to the kind of “he loved his mum” hagiography beloved of people who write about East End gangsters. Cromwell might not have been the butcher and bogeyman of legend, but he was an anti-Catholic religious fundamentalist, nonetheless. Still, for those interested in the subject, and what really happened in 1649, Cromwell was Framed is worth a peek. ~ The Catholic Herald